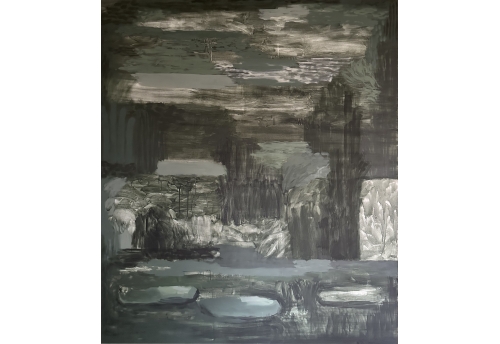

Bonnie Colin

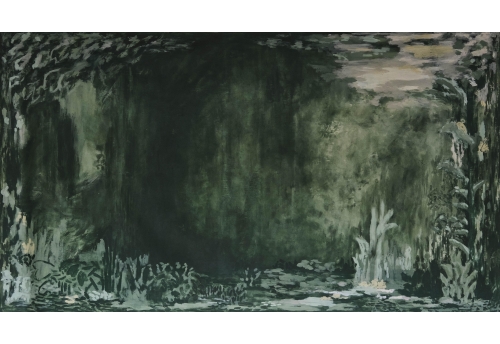

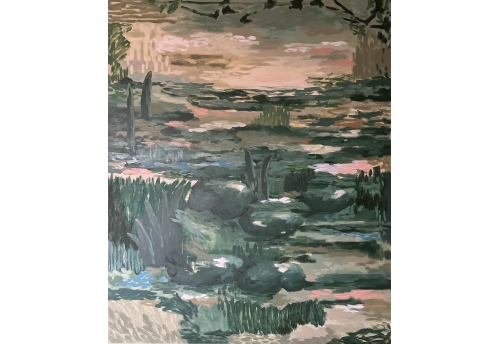

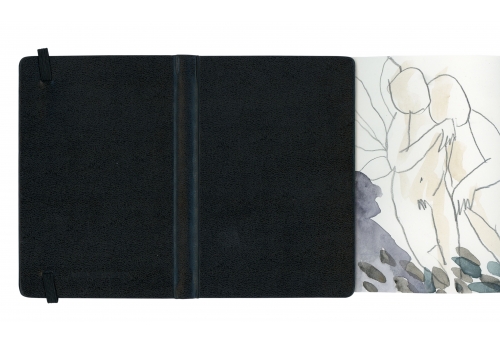

Bonnie Colin

Un grand enlacement

$ 12,000

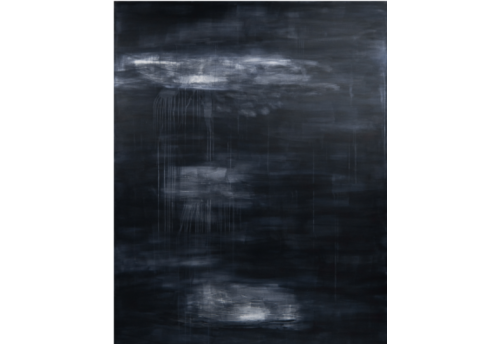

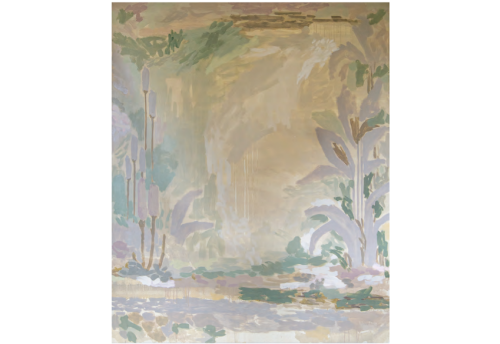

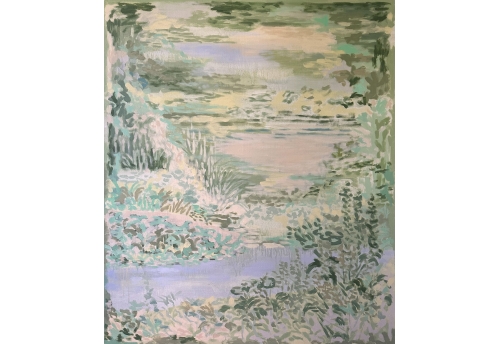

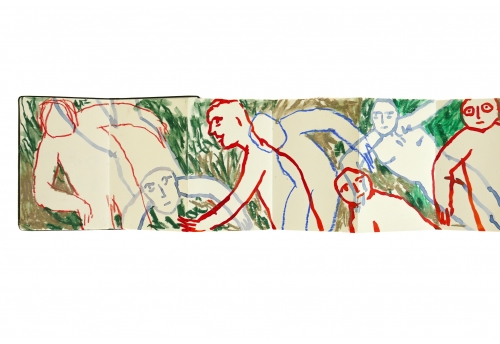

Bonnie Colin

Sarabande

$ 12,000

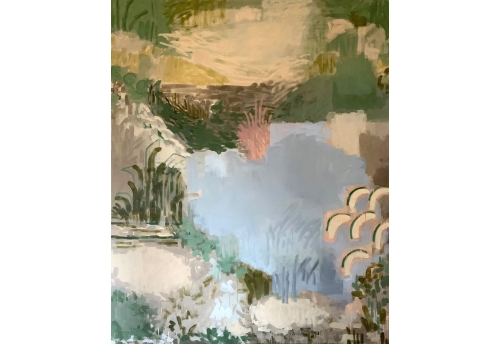

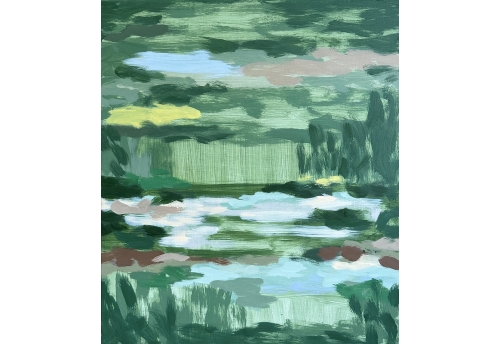

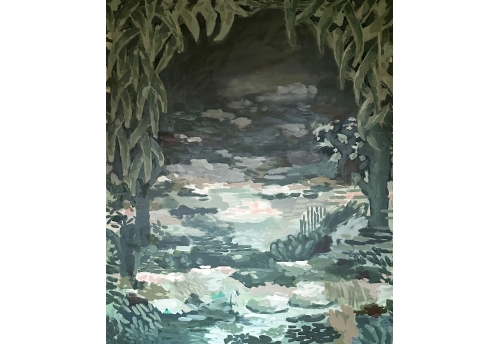

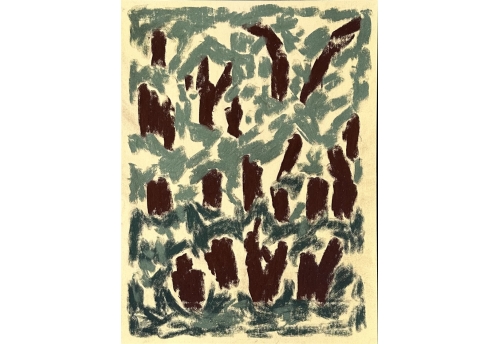

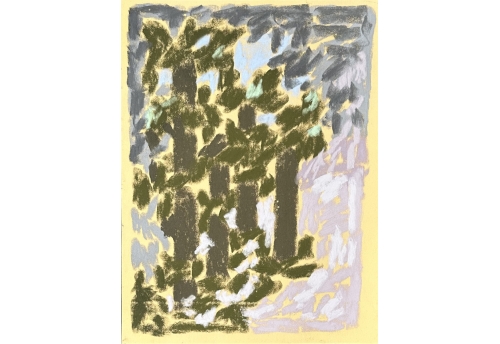

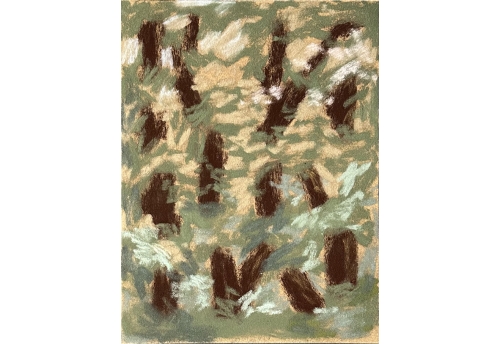

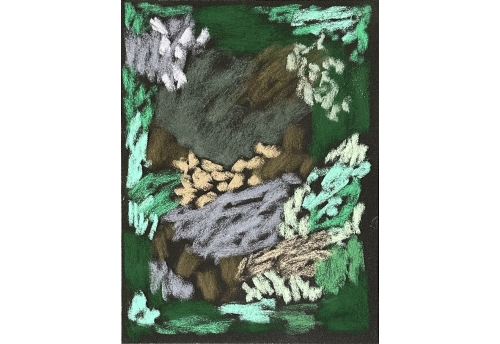

Bonnie Colin

Saudade

$ 12,000

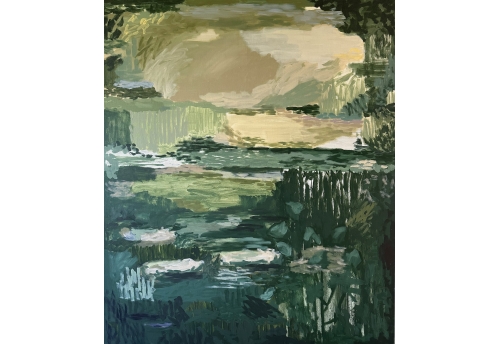

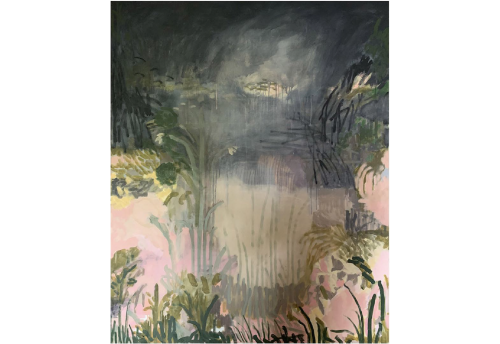

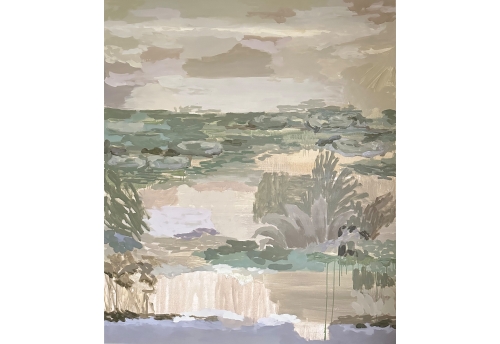

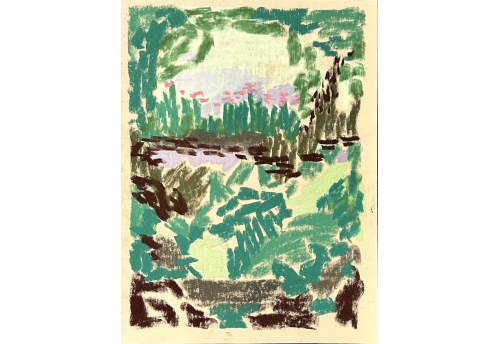

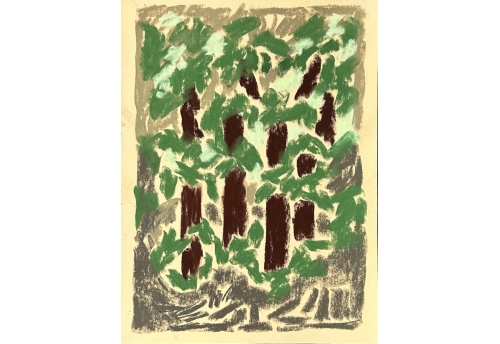

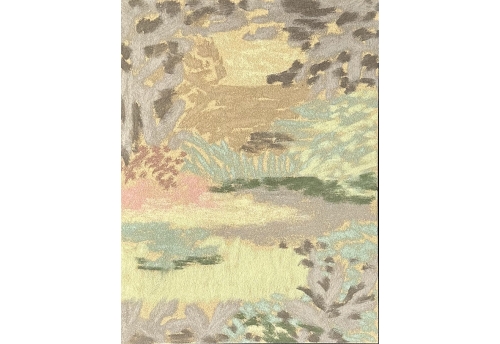

Bonnie Colin

Herbarium

$ 12,000

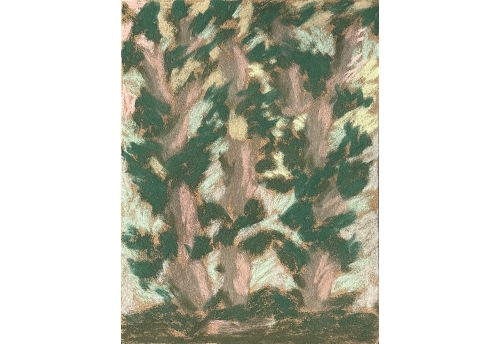

Bonnie Colin

Square 1

$ 11,400

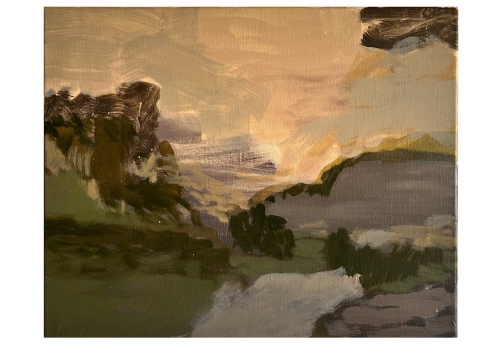

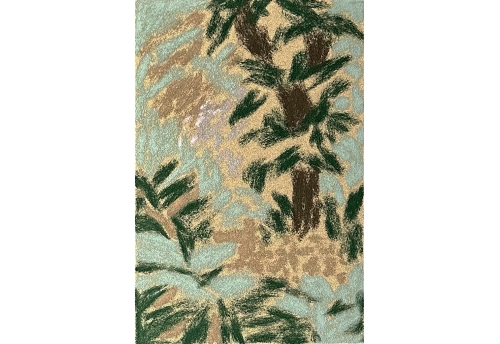

Bonnie Colin

End of the day in summer

$ 11,200

$ 11,200

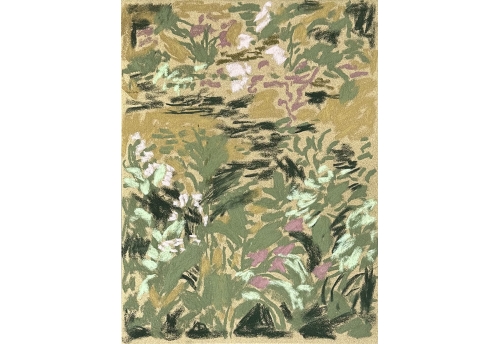

Bonnie Colin

Primavera variation 2

$ 11,200

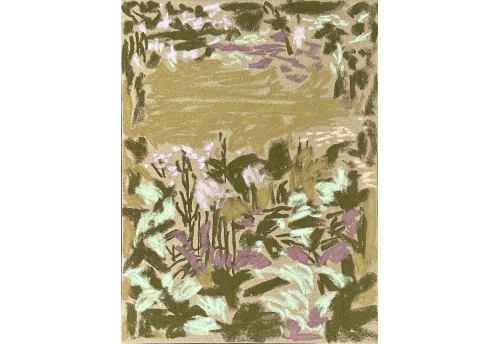

Bonnie Colin

Primavera variation 1

$ 11,200

$ 11,200

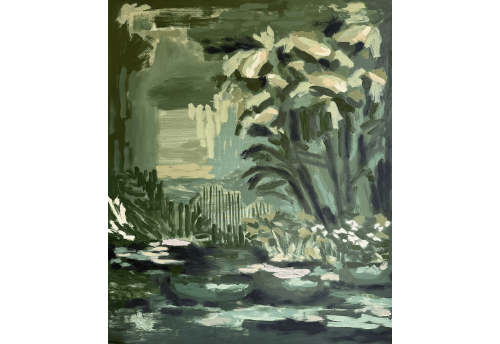

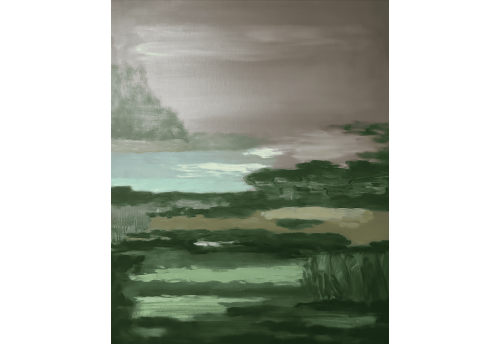

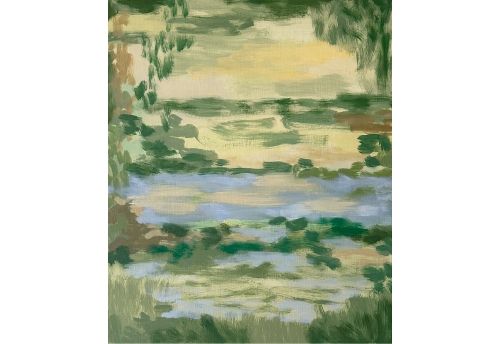

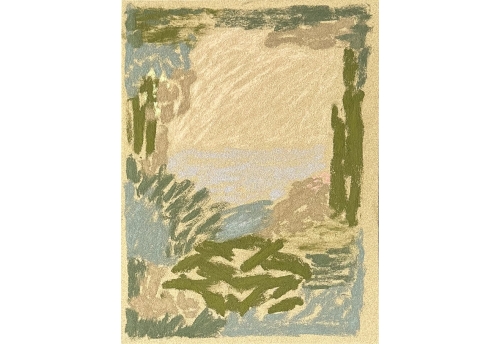

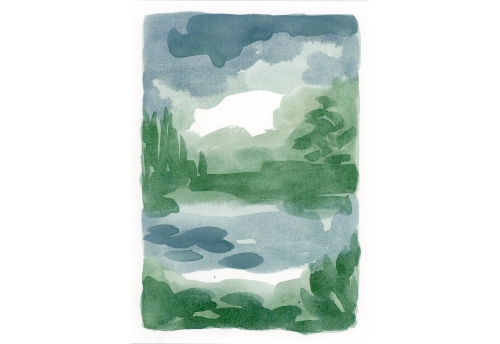

Bonnie Colin

Waterside dusk 2

$ 11,200

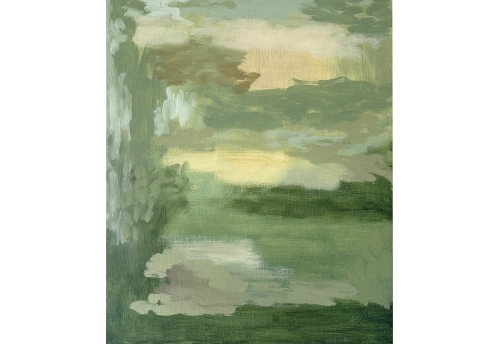

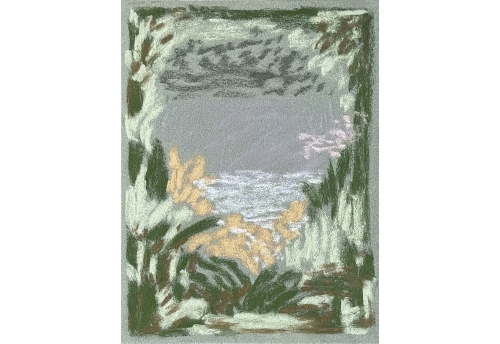

Bonnie Colin

Summer 1

$ 11,200

Bonnie Colin

Italie

$ 11,200

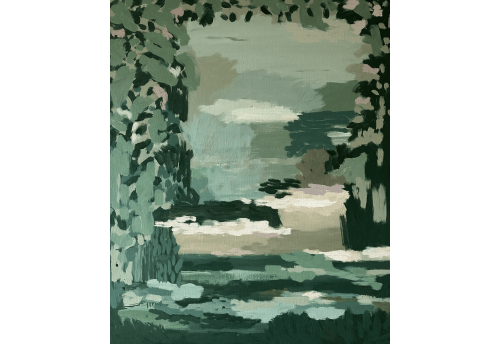

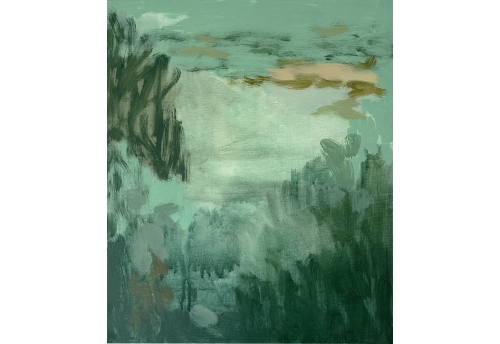

Bonnie Colin

Green waterside

$ 11,200

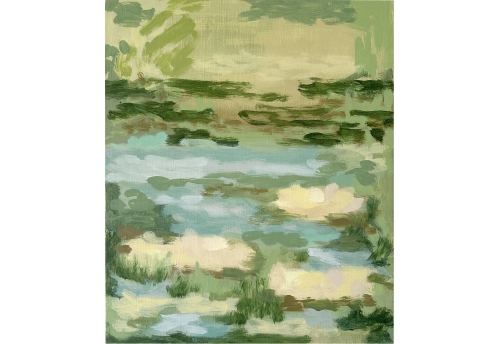

Bonnie Colin

Spring River 03

$ 11,200

$ 11,200

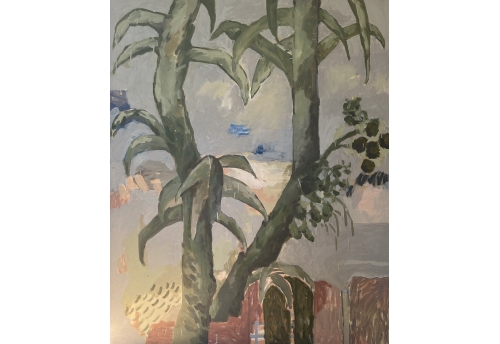

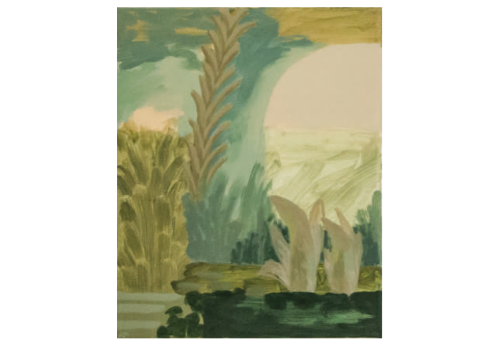

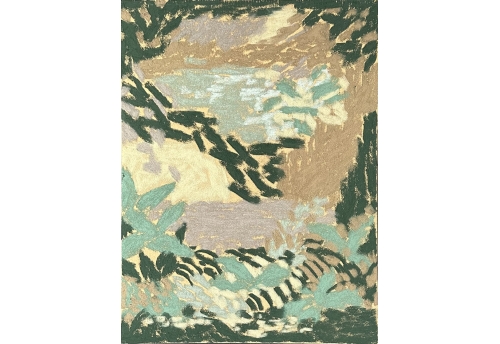

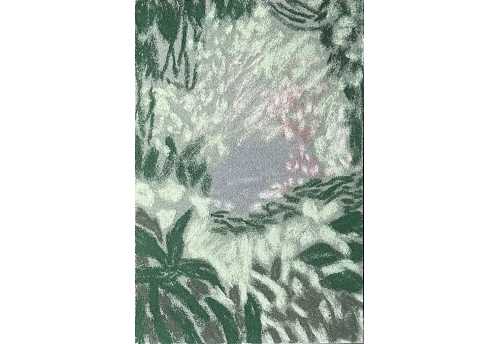

Bonnie Colin

Amazon memories

$ 7,000

Bonnie Colin

Waterside 12

$ 6,500

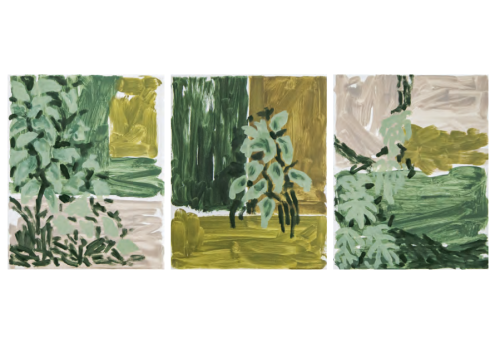

Bonnie Colin

Petites Genèses 25 & 26

$ 6,500

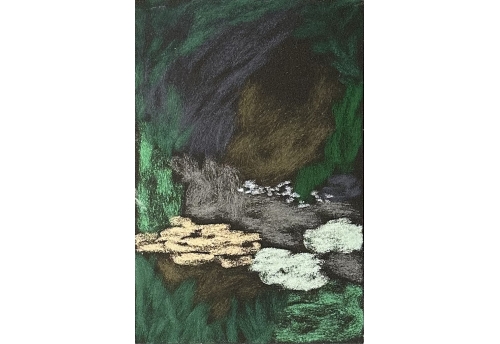

Bonnie Colin

Waterside 11

$ 6,500

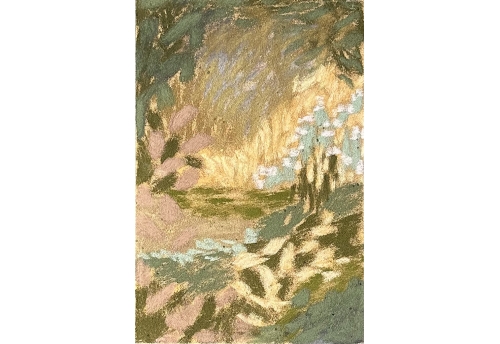

Bonnie Colin

River flow 4

$ 6,500

Bonnie Colin

Little green frog song 2

$ 6,500

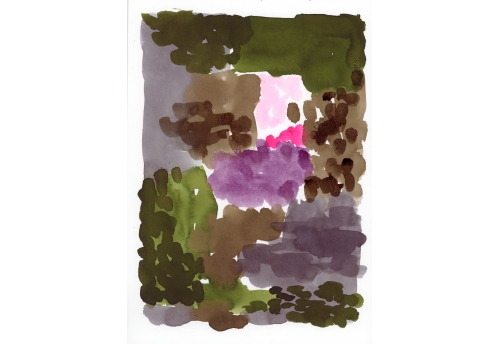

Bonnie Colin

Bouquet 01

$ 6,500

Bonnie Colin

Edge of the wood 10

$ 6,500

Bonnie Colin

Little frog song

$ 6,500

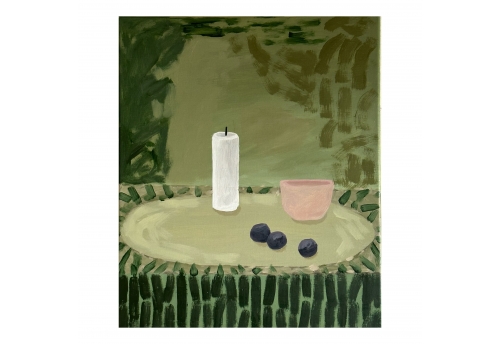

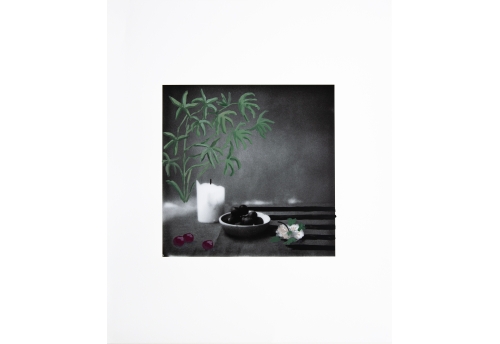

Bonnie Colin

Nature Morte

$ 4,000

Bonnie Colin

Petit Waterside 2

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

Petite Genèse 28

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

Petite Genèse 27

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

Countryside 11

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

Tribute to an angel - Jaco

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

Tribute to an angel - David

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

Tribute to an angel - Jean Paul

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

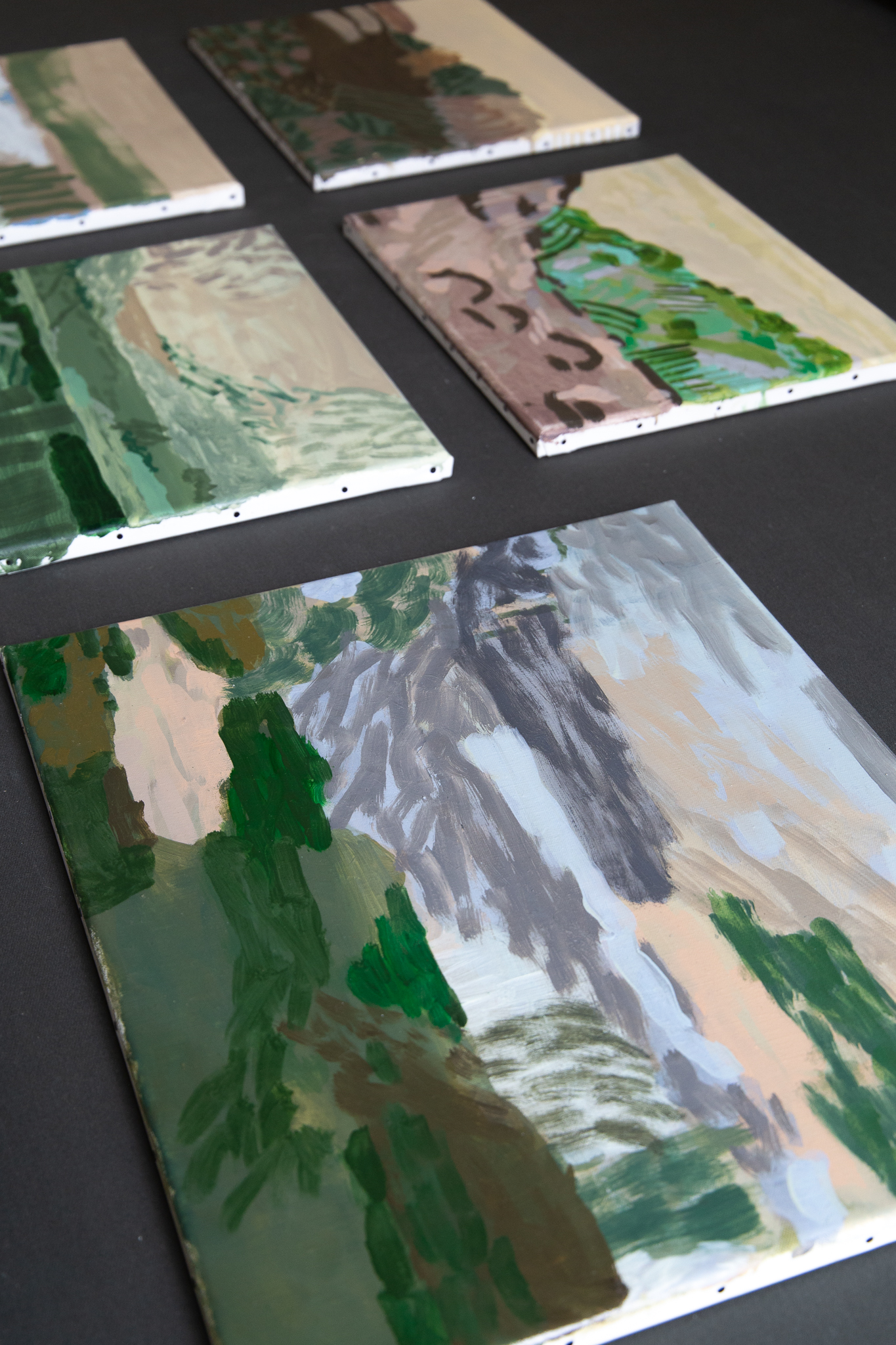

River flow 7

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

River flow 6

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

River flow 5

$ 3,500

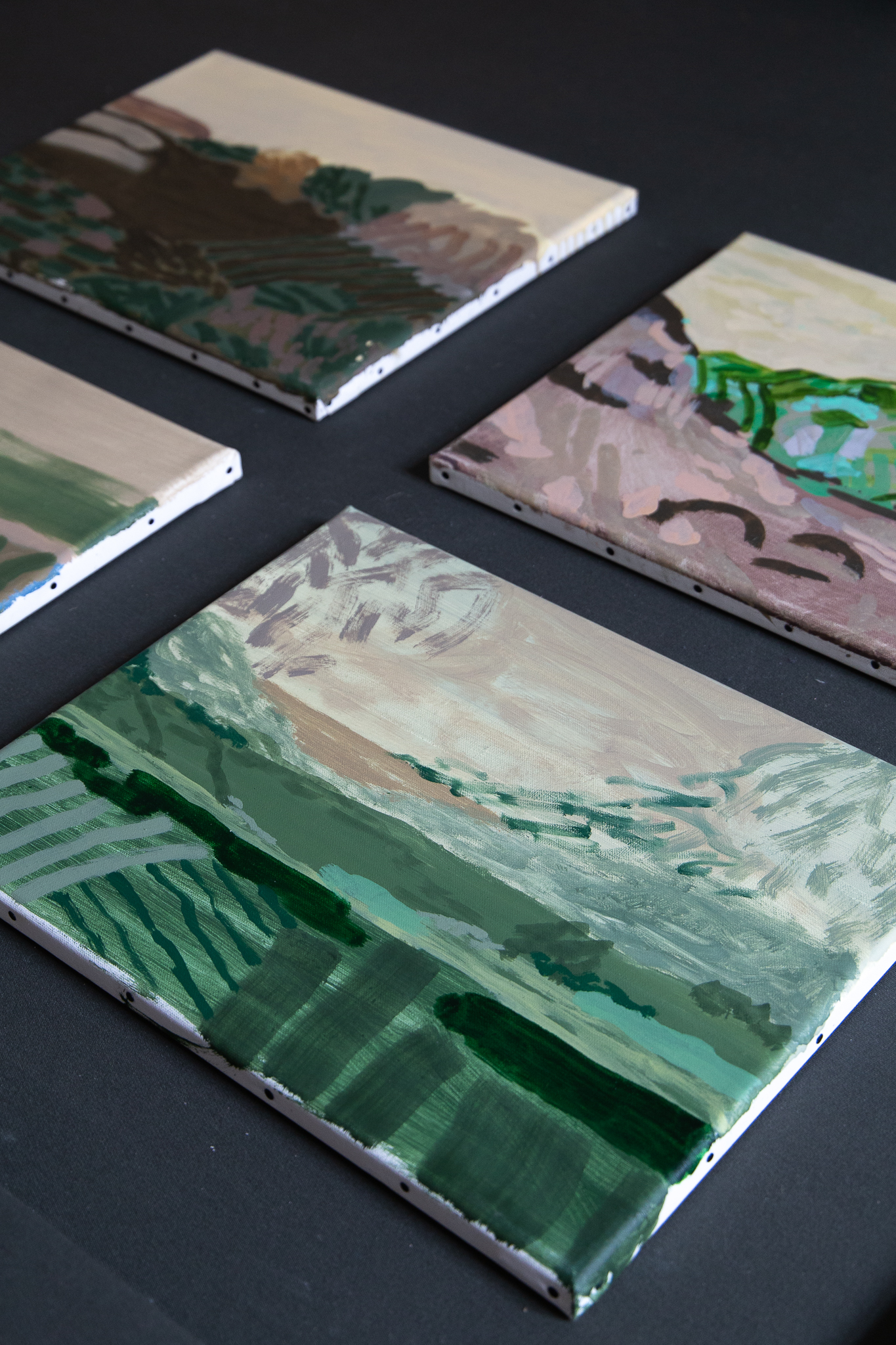

Bonnie Colin

River flow 2

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

Focus 3

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

Fields 2

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

Like a spring 1

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

Focus 2

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

Summer 3

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

Summer 2

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

Summer 1

$ 3,500

Bonnie Colin

Blur 4

$ 3,200

Bonnie Colin

Blur 5

$ 3,200

Bonnie Colin

Petit requiem 2

$ 3,200

Bonnie Colin

Blur 3

$ 3,200

Bonnie Colin

Little thing 3

$ 3,000

Bonnie Colin

Latitudes 23

$ 3,000

Bonnie Colin

Latitudes 14

$ 3,000

Bonnie Colin

Latitudes 24

$ 3,000

Bonnie Colin

Latitudes 26

$ 3,000

Bonnie Colin

Latitudes 20

$ 3,000

Bonnie Colin

Nature morte 7

$ 2,900

Bonnie Colin

Sweet 21

$ 2,900

Bonnie Colin

Nature morte 6

$ 2,900

Bonnie Colin

Nature morte 5

$ 2,900

Bonnie Colin

Nature morte 4

$ 2,900

Bonnie Colin

Nature morte 3

$ 2,900

Bonnie Colin

Nature morte 2

$ 2,900

Bonnie Colin

Nature morte 1

$ 2,900

Bonnie Colin

Sweet 01

$ 2,900

Bonnie Colin

Sweet 06

$ 2,900

Bonnie Colin

Sweet 07

$ 2,900

Bonnie Colin

Sweet 08

$ 2,900

Bonnie Colin

Sweet 18

$ 2,900

Bonnie Colin

Sweet 19

$ 2,900

$ 2,800

Bonnie Colin

Sugar 02

$ 2,500

Bonnie Colin

Sugar 20

$ 2,500

Bonnie Colin

Sugar 07

$ 2,500

Bonnie Colin

Sugar 23

$ 2,500

Bonnie Colin

Sugar 19

$ 2,500

Bonnie Colin

Sugar 14

$ 2,500

Bonnie Colin

Sugar 13

$ 2,500

Bonnie Colin

Sugar 12

$ 2,500

Bonnie Colin

Papier 01

$ 2,400

Bonnie Colin

Baby 15

$ 2,000

Bonnie Colin

Baby 21

$ 2,000

Bonnie Colin

Baby 24

$ 2,000

Bonnie Colin

Baby 23

$ 2,000

Bonnie Colin

Baby 22

$ 2,000

Bonnie Colin

Baby 18

$ 2,000

Bonnie Colin

Baby 10

$ 2,000

Bonnie Colin

Baby 06

$ 2,000

Bonnie Colin

Baby 02

$ 2,000

Bonnie Colin

Ozone 8

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Ozone 7

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Ozone 6

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Ozone 5

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Ozone 4

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Ozone 3

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Ozone 1

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Ozone 2

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Tondo 7

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Tondo 2

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Papier 16

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Tondo 1

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Tondo 6

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Tondo 3

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Tondo 5

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Tondo 4

$ 1,900

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 13

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Bouquet 10

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 10

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Bouquet 11

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 11

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 12

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 15

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 14

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 16

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 9

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Ozone 14

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Ozone 15

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Ozone 16

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Ozone 13

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Bouquet 08

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 8

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 3

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Bouquet 01

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 1

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Bouquet 02

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 7

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Bouquet 03

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 2

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Bouquet 04

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 4

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Bouquet 05

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 5

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Bouquet 06

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Les encres 6

$ 1,700

Bonnie Colin

Candy 06

$ 1,600

Bonnie Colin

Candy 36

$ 1,600

Bonnie Colin

Candy 39

$ 1,600

Bonnie Colin

Candy 44

$ 1,600

Bonnie Colin

Candy 46

$ 1,600

Bonnie Colin

Candy 54

$ 1,600