Philip Guston at the Musée Picasso

At the Musée Picasso, the Philip Guston exhibition opens as a quiet yet charged space, where painting always seems to stand on an edge. The rooms recount the journey of an artist who moved from abstraction to a direct, slightly awkward figuration at times almost childlike, yet astonishingly powerful.

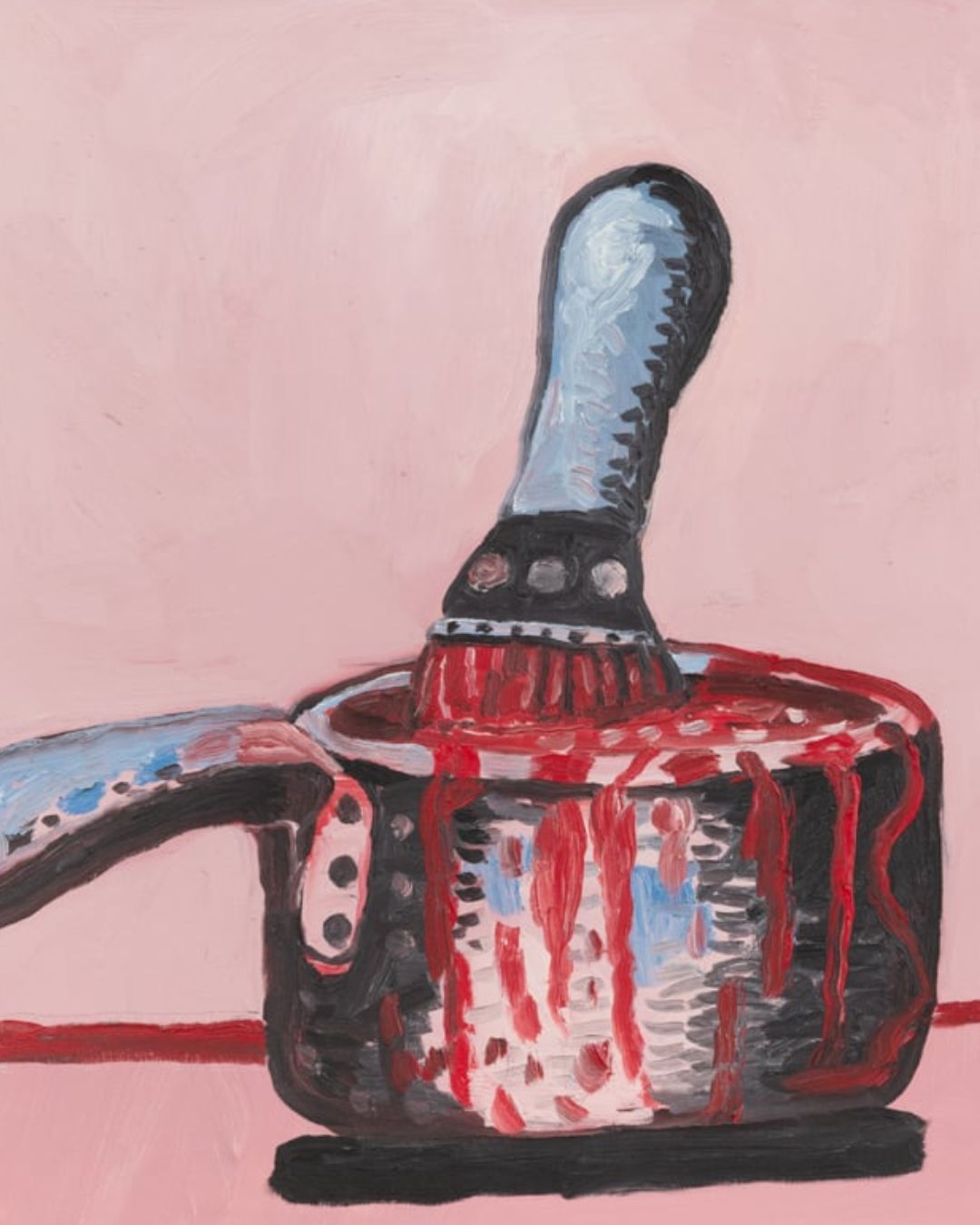

The early paintings resemble inner landscapes: large pinkish fields, floating gestures, thick surfaces still vibrating with the energy of American painting of the 1950s and 60s. The colors stretch, overlap, and retain something restrained. Then, from one room to the next, abstraction begins to crack. Forms return, lines sharpen as if the outside world were gently insisting on reappearing.

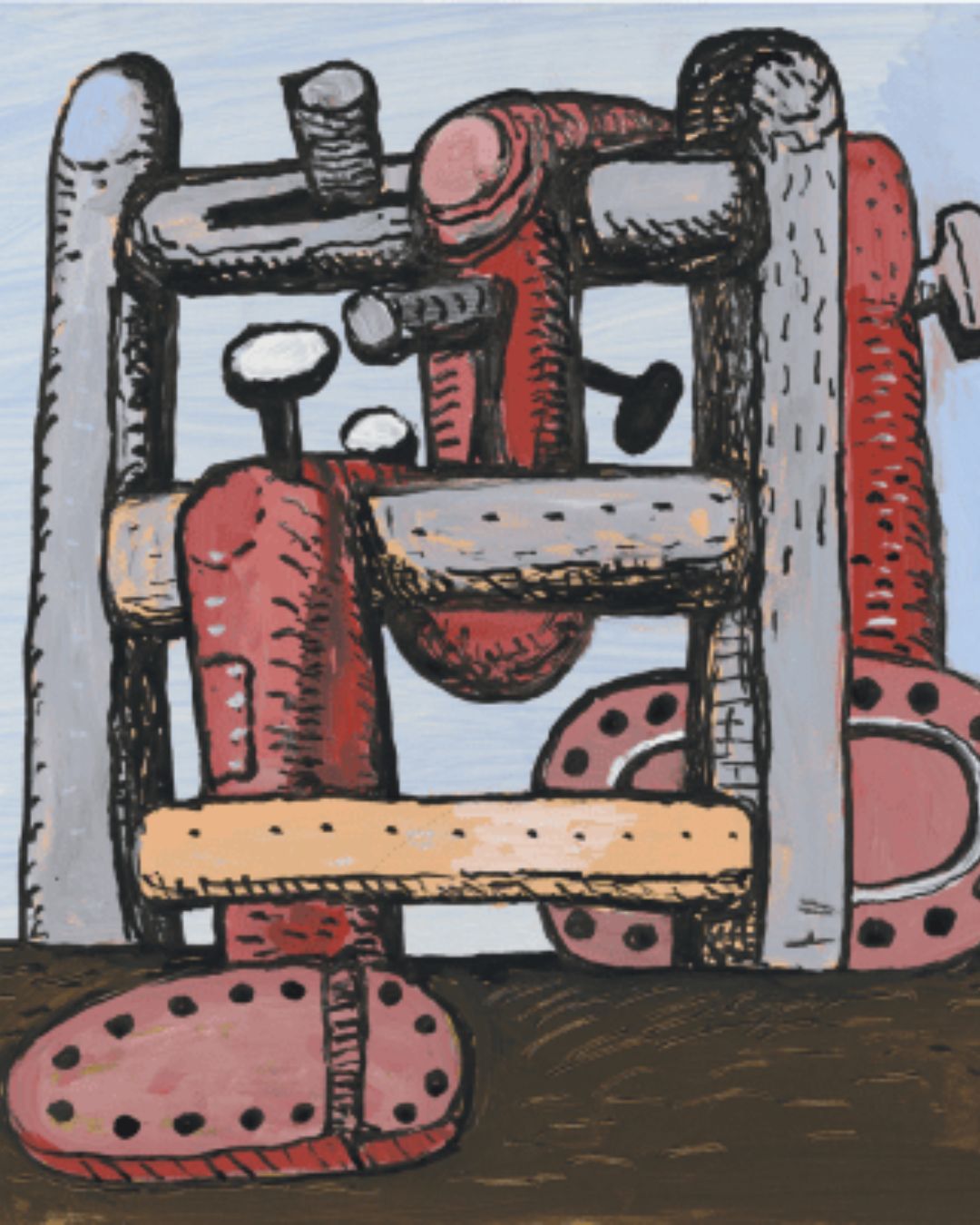

Then comes the turning point. Those hooded figures, those shoes dragging across the floor, those lamps, those oversized cigarettes, those walls set down like heavy blocks. The painting becomes more direct, less decorative. It speaks of what disturbs, of what weighs on us: violence, racism, fear. It also reveals the absurdity of the everyday that unintentionally humorous edge that slips into the images.

Between two works, a breath. A light pink, a rawer red, a dust-colored grey: everything seems to sway slightly. The black line thickens, sometimes trembles, like a blurred memory or a dream one can’t quite hold onto. Objects appear alive, bodies disappear. The works retain an insistence, a pulse.

Further on, the drawings accumulate, all trial, return, hesitation. The pencil begins again, hesitates, corrects. Nothing is fixed in Guston’s work: everything can still shift, change. Painting becomes a way of resisting forgetfulness, of staying awake in a world that tires quickly.

As the visit unfolds, a strange sensation settles in: the feeling of moving through something deeply sincere, without effects, without protection. The museum becomes a place where dark humor and gravity answer one another without contradiction.

Stepping back outside, the Paris light seems slightly altered, as if filtered through Guston’s colors and contours. In the street, an echo lingers, soft and rough at once: the certainty that painting can still move things, open a space, overturn a gaze, and begin again.